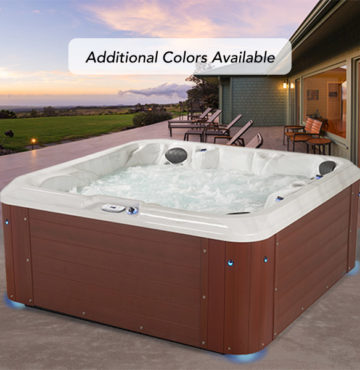

Acrylic Hot Tubs

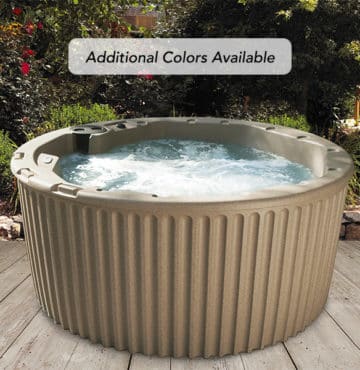

Resin Hot Tubs

Lounger Hot Tubs

Non-Lounger Hot Tubs

Welcome to MyHotTub.com – Your Partner in Relaxation and Wellness

At MyHotTub.com, we are passionate about making the luxury and comfort of hot tub ownership accessible to everyone. As part of our commitment to delivering the best value and quality in the industry, we are thrilled to announce that we’re now offering Aqualife Spas by Strong Spas. With these two exceptional brands under one roof, you can experience a wide range of options tailored to meet your unique needs—all at unbeatable prices.

Two Brands, One Great Hot Tub Experience

When you choose MyHotTub.com, you’re choosing quality, innovation, and affordability. Our expanded lineup now includes the trusted craftsmanship of Aqualife Spas by Strong Spas. Both brands embody the superior manufacturing standards and attention to detail that define our Pennsylvania heritage, offering options for every budget and lifestyle. Strong Spas: Renowned for their reliability and cutting-edge design, Strong Spas delivers premium features and luxurious details for those seeking the ultimate hot tub experience. Aqualife Spas: Perfect for families and first-time hot tub owners, Aqualife Spas combines high performance and affordability, making it easy to enjoy the benefits of hydrotherapy without breaking the bank.

Together, these two brands offer a seamless range of options—from budget-friendly models to high-end luxury spas—all backed by decades of Pennsylvania manufacturing expertise.

Why pay more when you don’t have to? By purchasing directly from MyHotTub.com, you’ll enjoy factory-direct pricing that eliminates middleman markups and guarantees the best value for your investment.